One name has kept popping up in design circles in recent years. He is said to be one of the greats but also someone who tends to avoid the limelight. Now, however, several of his furniture projects have been put into production by the Danish manufacturer A. Petersen.

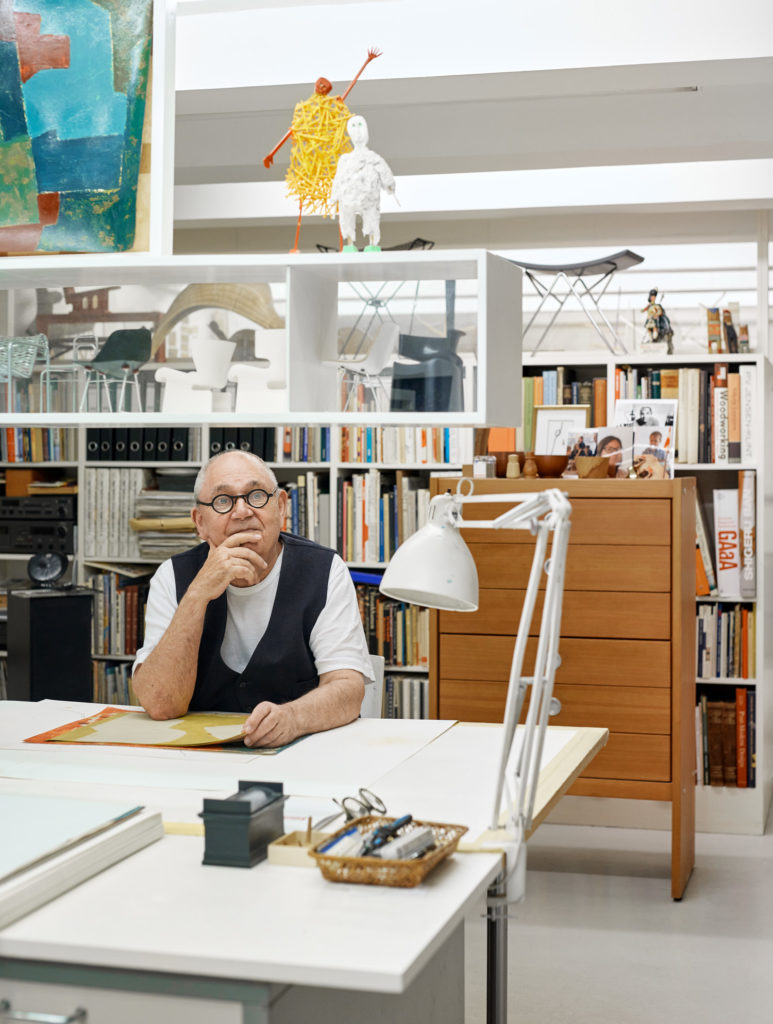

Many years ago, Dan established a drawing office and workshop, separated by shelving units, underneath his living room. At the desk he designs new furniture or paints abstract paintings, as can be seen at the top of the floating shelf.

It is clear to see that there is great respect for the man who, as the only person, was allowed to work for and run the design studio of Poul Kjærholm, in addition to teaching at the Royal Danish Academy – School of Architecture for nearly a lifetime. We visited architect Dan Svarth in his home and studio in Copenhagen’s Østerbro district.

Dan Svarth looks surprised as he opens the door, and for a moment I worry that I got the date wrong. Nevertheless, I am waved into a long hallway as he mumbles something about being instructed that he simply MUST let me visit, even though he sounds fairly sceptical of the whole idea. On the walls hang large plaster casts of ancient Egyptian friezes and ornaments.

Dan continues into the living room, only to come to a stop in the middle of it, as the treasure chamber of a room begins to open before my eyes. Classic Herman Miller furniture stands side by side with Dan’s own designs.

A wealth of historical artefacts and objects cover most of the surfaces, testimony to Dan’s passionate interest in the golden age of Egyptian furniture design. The walls are covered with paintings, drawings and tapestries, the latter created by Dan’s wife, textile designer Anet Brusgaard.

He seems somewhat uneasy about the visit but relaxes slightly when asked about his time at the Academy (the Royal Danish Academy – School of Architecture in Copenhagen), where he enrolled as a student in 1968 and, directly after finishing his education, continued as a teacher until 2006.

‘The Academy was no kindergarten. It was up to you to decide if you wanted to engage or not. Whether you felt you had anything sufficiently important yo bring forth to the professors. If you didn’t, there was no reason to waste their time, and they would make sure to let you know. Then you could go home and rethink. That’s also why many students didn’t much like the Academy – at least not the Department of Furniture Design.’ The study of architecture during the 1970s was quite different from what it is now. Studying was mostly self-directed by the individual students, and it did not have the current regular structure of a three-year bachelor’s degree followed by a two-year master’s. Back then, you had to humbly request permission from your professor to be allowed to spread your wings, after which it was up to the professor whether you would be allowed to embark on your final assignment, or whether you might simply be notified that you were not yet ready but were to kindly continue your studies without the promise of a fixed end date. In the worst case, you might be told there was no reason for you to continue, Dan recalls. This brought to mind some of the toe-curling stories in circulation at the Academy when I was a student there myself, including ones featuring the architect Poul Kjærholm, one of the most prominent professors of his time and known for being particularly uncompromising – but that is about as far as I get before Dan interjects:

‘Well, you have to be! Compromises lead nowhere. In reality, he was great. He has been completely misunderstood.’

Dan says that last sentence more to himself, as he has already turned his back on me and is heading towards the stairs in the back of the living room, which lead downstairs to his drawing office and workshop. In this room, which is as large as the combined living and dining room upstairs, there are towering stacks of books, drawings and hundreds of scale model chairs. A central desk is placed on top of a classic filing cabinet. Above hangs a floating shelf with even more models. Behind a partition made of bookcases lies Dan’s workshop, where he creates meticulously detailed chair models, amongst other things. ‘After some years at the Academy, I asked Poul [Kjærholm] whether I might be allowed to graduate. He didn’t see the point. He advised me to get out and design some furniture. Just a few days later, he rang me to ask if I would like to teach at the Academy one day a week. Shortly afterwards, I also began to work at his drawing office,’ says Dan.

Perhaps it is the well-worn PK11 chair, designed by Kjærholm, pushed in under a small table along the wall that brings him back to the story.

‘I took over his studio after some time. He didn’t feel like drawing, which I can certainly understand. It’s easier to explain what you want, and where you want to go, and then get others to draw it. That allows you to maintain the wider perspective. You don’t get lost in the details. That’s what you see in the TV programme Danmarks Næste Klassiker (Denmark’s Next Classic), where the participants lose themselves in details. Poul didn’t care for that. Lucky thing, because otherwise everything would get derailed.’

I notice a twinkle in Dan’s eye as he looks up and catches my gaze. Now I am the one who is surprised that the architect is referencing the Danish broadcasting corporation DR’s recent reality TV series, in which furniture designers compete to create a new furniture classic in just three weeks. ‘How about a cup of coffee?’ he suggests, jovially. As we head up the stairs and into the kitchen, Dan returns to the topic of his time with Kjærholm. ‘If you didn’t understand the tone, the importance, the character of the work, you couldn’t work for him. But I never had any problems understanding what Poul wanted to achive.’ In an attempt to understand the size of the iconic architect’s design studio, I ask about the other employees. ‘Well, it was just me!’

Seated at the kitchen table with a cup of black coffee in front of me, my eye is drawn to the impressive plaster casts adorning the walls.

‘I believe you’re dependent on the things that happened in the past. It’s important to be mindful of history. I myself am very dependent on it, and almost always use something from the past as my starting point. Not just that of other colleagues. I mean real history. Chinese, Egyptian, Roman, Spanish and so forth. You see a piece of furniture, and then you try to improve it. To refine it,’ says Dan.

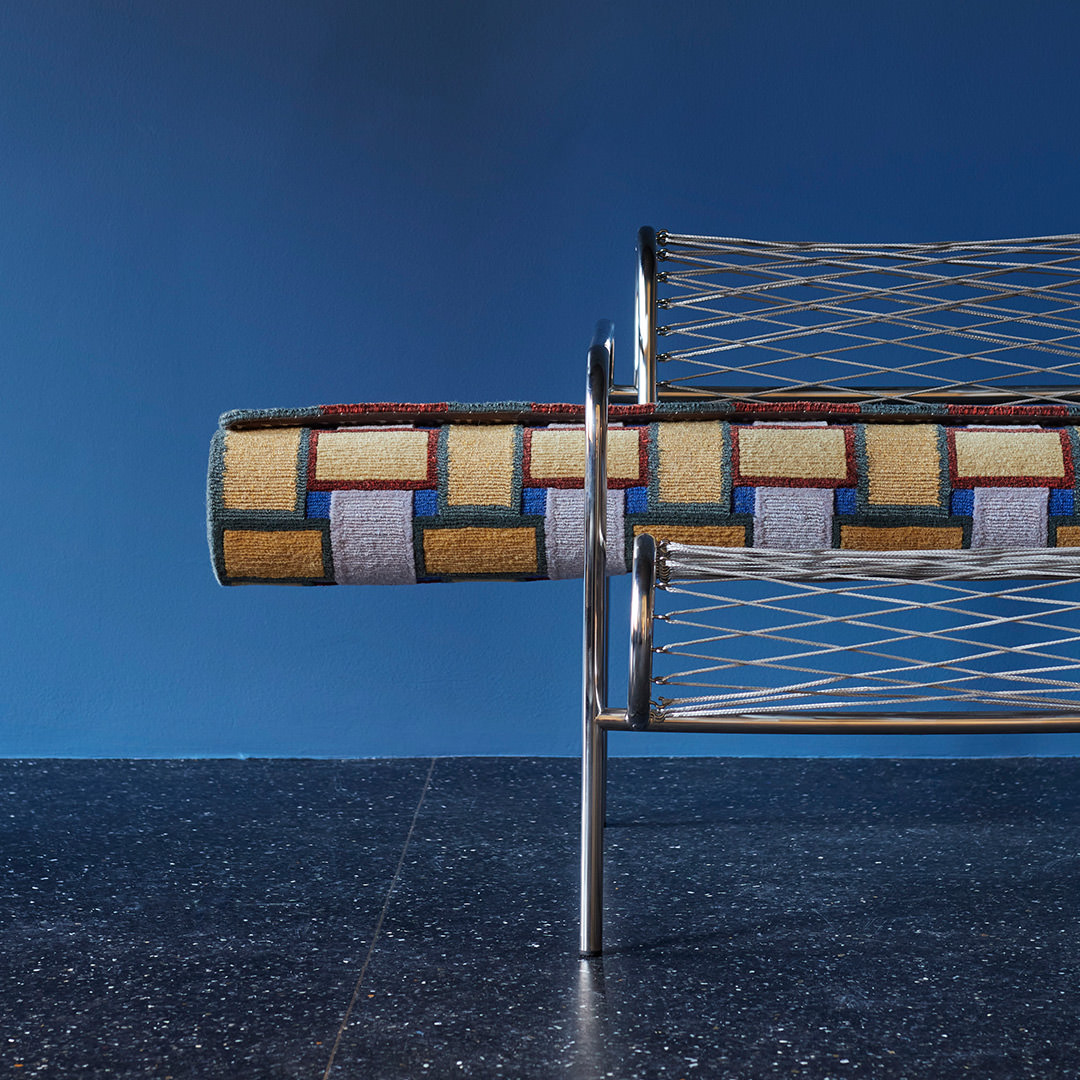

Alongside his nearly 40 years at the Academy and in Poul Kjærholm’s office, Dan also worked on designs of his own, as evidenced by the impressive collection of models in the basement. Only a few of his designs have been put into production, until Anders Petersen from A. Petersen laid eyes on this hidden treasure trove just over five years ago. Since then, he has put both new and older designs by Dan into production. While a sofa, a rocking chair and a number of tables are new designs, the Wire Chair, which will be launched in the near future, was originally designed in 1972.

‘I don’t get tired of a design, but I can tell that it’s old. It was a different time. Back then, all the architects had a fairly similar design expression. We drew inspiration from each other and tried to do better. We pushed each other in this direction or that. But it isn’t like that anymore. That relationship isn’t there anymore. Now, it points in all directions.’

Was it better back then?

‘I couldn’t say whether it was better, but it was better for the art of furniture making. That is basically nonexistent today. When it becomes really commercialized, it takes on a completely different character. It’s like there is no relationship there anymore. Culture is based on refining things, but people don’t think about that in design anymore.’

Why do you think that is?

‘There are no guidelines anymore. People don’t know in which direction to go. And then the design begins to loosen. It’s common to talk about whether something is beautiful. But what is beautiful? That is a matter of judgement. Of course, you can develop your own criteria and make them sublime in many ways. But no one does that anymore, now that the materials and techniques can do whatever you want them to.’ When you design a new piece of furniture today, is it still for the sake of improving it?

‘I definitely aim to do as well as I can. And that’s why I can’t create anything in three weeks, as you see in Danmarks Næste Klassiker, for example. I take much longer. I hang it up and observe it for a long time. Then I take it down and do some more work on it, and then I hang it up again. It continues like that for a long time.’

Do we even need more chairs?

‘No … but that’s what’s so great about culture. It changes. If culture is not renewed, it has no meaning.’ That last sentence fills the ensuing silence in the room, before Dan lets out a laugh.

‘If culture is not renewed, it has no meaning.’

Dan Svarth

‘Oddly, when we speak about chairs, we rarely speak of renewal. But look at stage plays, for example. Those are renewed continually, every time a classic is performed anew. That’s what I mean by striving to refine a piece of furniture.’

The chairs and dining table were both designed by Dan. The latter was recently put into production by A. Petersen. The Hanging Lamp is a Gerrit Rietveld design, and the totem-like sculpture in white is one of Dan’s early works. The works on the wall are by Lise Malinovsky.

Over the past 35 years, Dan has been conducting a comprehensive research project dealing with the earliest known furniture designs from ancient Egypt, starting from around 3000 BCE. A time when art, architecture and crafts underwent explosive development.

‘Consider the Egyptians. They invented the reclining backrest. The lounge chair, an extraordinary invention! And perhaps you’re thinking, “settle down, you old fool”, but wasn’t that radical? And when they began to carve the back leg so it was narrower where it connects with the backrest, that was exclusively for the sake of appearance. Otherwise it would look clumsy. It is a purely aesthetic experience.’

Is it okay to design exclusively with aesthetics in mind? ‘Yes, of course! But you shouldn’t talk about it too much.’

We share a laugh, as we both know that if there is one thing that is prohibited at the Academy, this is it. Even though it seems the most natural thing in the world when one is born with an eye for visual expression.

Part of Dan’s research involved visits to historical museums the world over, where he carefully studied and recorded furniture from Egyptian tombs. Based on these studies, he created perfectly detailed 1:5 scale models of all the chairs known from ancient Egypt. The more than 100 models were all created in the workshop under Dan’s home.

‘It is pure style. The Egyptian priests who were involved in developing these chairs must have been great aesthetes. They knew exactly what they were doing. Old things can certainly feel relevant. Their sense of texture or form can be so unique,’ says Dan. That his comprehensive work with the models, apart from being immortalized in the reference work First Movers, would also end up as an exhibition, in 2019, at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, which possesses the most comprehensive collection of these exact pieces of furniture, is baffling to Dan. It seems completely out of the question that he would have his work exhibited at one of the world’s most renowned historical museums, but Dan’s body of work is full of surprises and accolades. He has been able to give back to history what it has given him. Almost a form of symbiosis. ‘At the Academy, we always believed that culture should be renewed. It isn’t all on you – you don’t stand alone in the world. We stand together.’